Richfield Tannery

RICHFIELD tannery

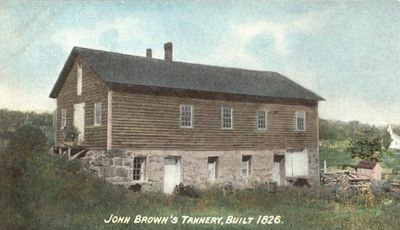

When John Brown lived in Richfield, he operated a tannery. While the building no longer exists, it probably looked much like the above pictured tannery he built in Penn. just a few years before. The Richfield tannery was located on the west side of Brecksville Rd. just north of Streetsboro Rd. It was to prove a vital industry in the growth of town. The rich fields of Richfield pastured an abundance of cattle and sheep, and their hides were very valuable when tanned. His business became so busy by 1844 that he could not handle all the business that came his way. The hides he produced were used in the collar shop (which still stands) and the many harness shops in Richfield Township and nearby towns, for shoes, boots, saddles, harness for horse and oxen, and more. The rest were shipped on the recently opened Ohio-Erie Canal (just down the hill from Richfield) to cities east.

The tannery stood close by two of the homes where the Brown's lived, a smaller cabin directly behind the tannery, and later a much more substantial house, that still stands, just down the road. John Brown and several of his sons worked there. It was brutally hard (and very smelly) work. As John Jr. wrote of those times:

"My first apprenticeship to the tanning business consisted of a three years' course of grinding bark with a blind horse. This, after months and years, became slightly monotonous. While the other children were out to play in the sunshine, where the birds were singing, I used to be tempted to let the old horse have a rather long rest, especially when father was absent from home; and I would join the others at play. This subjected me to frequent admonitions and to some corrections for 'eye service,' as father termed it. I did not fully appreciate the importance of a good supply of ground bark, and on general principles I think my occupation was not well calculated to promote a habit of faithful industry. The old blind horse, unless ordered to stop, would, like Tennyson's Brook, 'go on forever,' and thus keep up the appearance of business; but the creaking of the hungry mill would betray my neglect, and then father, hearing this below, would come up and stealthily pounce upon me while at the window looking upon outside attractions. He finally grew tired of these frequent slight admonitions for my laziness and other short comings."

"His father adopted a book account of the number of expected lashings for John Jr's. disobeying his mother, unfaithfulness at work and telling a lie." Then, "On certain Sunday mornings he invited me to accompany him from the house to the tannery, saying he had concluded it was time for settlement. We went to the upper or finishing room, and after a long and tearful talk over my faults, … I paid about a third of my debts, reckoned in strokes from a nicely prepared blue-beech switch, laid on 'masterly'."

"Then, to my astonishment, father stripped off his shirt, and, seating himself on a block, gave me the whip and bade me 'lay it on' to his bare back. I dared not refuse to obey, but at first I did not strike hard. 'Harder!' he said; 'harder, harder!' until he received the balance of the account. Small drops of blood showed on his back where the tip end of the tingling beech cut through. Thus ended the account and settlement, which was also my first practical illustration of the Doctrine of the Atonement."

It was said that Brown would not sell leather from his tannery until the last drop of moisture had been dried out of it, "lest he should sell his customers water instead of leather." A later apprentice at the tannery was to later bear testimony to the "singular probity" (the quality of having strong moral principles; honesty and decency) "of John Brown's life".

"Brown required his tannery workers to attend church and a daily family worship. One apprentice later described his employer as sociable, so long as 'the conversation did not turn on anything profane or vulgar.' Scripture, the apprentice added, was 'at his tongue's end, from one end to the other.'"

Tanning was considered a noxious or "odoriferous trade" and often relegated to the outskirts of town. And so it was in John Brown's time. Most of the houses and businesses were at some remove from his tannery, with most being at the crossing of Streetsboro Rd. & Brecksville Rd., while the tannery was a distance north.

A recipe that was used in Brown's time was as followed: Finely grind 30-40 pounds of oak bark. Boil 20 gallons of water. Mix together in a wood barrel and let stand for 15-20 days, stirring occasionally, then strain off the bark. Add two quarts of vinegar. Then hang the hides in the solution and move them around to insure even coloring. After 10 to 15 days, remove about 5 gallons of mixture and replace with fresh solution and an additional 2 qts. of vinegar. Soak for 5 more days, then remove 5 gals and replace the 5 gallons with fresh solution (add no more vinegar). Remove the hides after the 5 days and add 40 more lbs. of bark and replace hides. After 6 weeks, pour off half the bark solution and refill the barrel with fresh bark. Shake the barrel from time to time. When finished you should have harness or belt leather. Leave in mixture for another 2 months for shoe leather.

Following this recipe would have required a huge amount of bark, and a huge number of trees cut down to acquire it. There is a picture of Richfield taken sometime after the Civil War about which I have always wondered. In the picture you can see from the Fry Farm barn bridge all the way across the fields to "downtown" Richfield. There is barely a tree to be seen. I've always assumed that it was because the trees were cut to provide firewood in those days. But with John Brown building his tannery, the harvested trees probably served double duty. Firewood, ~and tanning bark. It's interesting that these 160 years later that all the surrounding woods have regrown and the center of Richfield can no longer be seen from our farm.

When John Brown moved the majority of his family from Richfield he left his son, Jason, behind to run the tannery. Son Frederick remained to herd the family sheep on the Oviatt Farm. This arrangement continued for a number of years.

Some years ago, in 1947, Brecksville Rd. was widened. During the excavation eight foundation stones for the tannery and six of the vats were uncovered. The six vats were in two rows running east to west between the foundation stones. About five feet wide, they were used to "pickle" the hides in tanbark. The road grading cut through more than a foot of the tanbark, which was still in good condition after a century underground. Horns of buffalo and cattle, skulls, bones and other refuse were also uncovered in profusion. Additionally they found ox shoes, a bed of charcoal, and an old dam across the stream at the rear of the property. They also found the front step stone of the long gone cabin. In the late 1940's a forgotten copper kettle was found in the basement of the building on the site of the tannery. In the kettle were some very dried and "ancient" sheep hides.

I walked that property one late winter day these nearly 180 years later. Those tannery foundation stones still sit close by where they have always been, the cabin step still lays under the pine trees just as it did back in that 1947 picture, and the stream carrying the water for tanning the hides was running strong. And, the vats surely are still buried partly under the "new" lane of Brecksville Rd. and partly just as they were covered over to level the present day side yard. ~~It almost felt as if John Brown might step along any moment.

Copyright © Jim Fry 2018