RICHFIELD ABOLITIONISTS

~~Being an abolitionist was a scary business. If you were caught you could be fined $2,000 by the Federal Gov't and an additional $1,000 by the State Gov't (that was real money in those days). You could go to jail. Local police were sometimes bribed to turn over known Abolitionists. Judges were often paid a $10 "reward" for every negro they declared a slave. You could be beat, or worse, if you interfered with slavers "repossessing" their "property". You could lose everything. As a consequence, folks didn't talk about what they were doing. No records were kept. No diaries written. You simply couldn't trust someone of whom you weren't absolutely sure. Anything you said, or did, or wrote, could be used against you in a court of law. ~~So there is not much known about how individuals running the Railroad operated. Fortunately there were exceptions.

THE MASON OVIATT FAMILY

The Mason Oviatt house stood on the north side of Streetsboro Rd., near the bottom of the very steep Hinckley Hill. Many years after the Civil War, Fannie and Mason Oviatt told one of their family stories to their grand-daughter, Jennie Oviatt. They relived the story, just as it had happened those years before, using the words and thoughts they remembered from that night. Jennie dramatized those events for those who might read of them later.

~

"Whatever are you putting a load of hay on the wagon at night for?" Fanny asked. Mason's eyes shifted down to his boots and Fanny checked an instinct to reach out and pat him. She loved every inch of his bigness. She had picked him out and married him from the five Oviatt boys, all over 6 feet tall and with muscle and brawn that could outlift anyone in Richfield Township, or Summit County for that matter.

She was sure he would be willing to stand up to anyone in the State of Ohio and she loved him for it. She wondered if she didn't love him more at times like this when he was shy and wouldn't face her because he had done something of which she might disapprove.

"I'm hauling it for Uncle Heman."

"Where to?"

"West a ways."

"As far as Oberlin?" Fanny's voice was frightened. "Mason Oviatt are you getting mixed up with John Brown and the runaway slaves? I'd almost as soon see you get mixed up with Mallet's counterfeiting gang," Fanny said. "Did you fix it so those poor men could breathe? They'll be half scared to death without smothering them, too."

Mason grinned at the change in her. "Don't worry. I'll get them there safe. I'll be gone three or four days." With a lift of his massive shoulders he went across the yard to the barn to put the team to the wagon.

The horses trotted smartly out the drive and turned east on the road. Their feet clattered on the plank bridge over the creek that fed into Rocky River. The sound carried to Fannie's ears.

Mason slowed the team for the grade over the natural bridge. It was all uphill through West Richfield and then down to the Center where the stagecoach road went through from Cleveland to Massillon. John Brown lived in the second house east of the Center, on the south side of the road.

"He ought to have stuck to tanning," Mason said to himself. "Hudson folks say he's the best tanner west of the Alleghenies. He's a good sheep herder too." Mason slowed the horses down and turned them in the drive. Jason, a tall lanky youth, the first of Brown's sons by his first wife, came out with a lantern and showed him where to turn the team and bring them back up to the house. The horses faced the road so that anyone passing could not see what was going on at the back of the wagon.

Jason blew out the lantern and said, "Father is in the house. He said for you to come in. I'll watch the team."

Mason went in to where John Brown was sitting wrapped in a quilt by the fire. He looked old, older than his forty-two years but perhaps that was because he was gaunt and thin. When he talked there was a glitter in his blue eyes that was brighter than the fire of fever. He gave his instructions concisely. "Do you understand --perfectly?" he asked.

Mason nodded.

"May God be with you and all that are in your care on this journey," prayed John Brown.

"Thank you, Mr. Brown."

At a nod from his father, John Jr. went down the inner steps to the cellar and Mason went out to the waiting wagon. Carefully he drew the hay away to disclose the false bottom he had built on the rack that afternoon. The moon would not rise for another hour. He heard the cellar door at his side open and half saw a dark head peering up.

"All right, man," he whispered and held down a hand. "Come on up. There's nothing to be afraid of here." Mason helped him wriggle into the shallow space cautioning him to keep over to the right as far as possible so as to leave room for the others. One after another, four men scrambled into the space between the load of hay and the floor of the rack.

Mason turned. But John Jr. touched him on the arm. "Here's another." "I thought there was only four," Mason said. "We can't get him in. They're tighter than pigs in a trough."

We've got to," John's whisper was urgent. "He came last night. It may be weeks before we go out again." The others moved still closer together and the little one quickly squeezed his way in. Mason stuffed a couple of armfuls of hay across the end of the box, and with his fingers combed the overhanging hay down to hide it.

There was nothing stirring in West Richfield and he gave the team its head on the two mile down grade to his place. Their hoofs clattered over the plank bridge and they started to turn in the home driveway, but he kept them steady on. He wanted to go in too, for Fanny came to the door and stood silhouetted with the oil lamp light at her back. He carried that picture with him all the long westward trip.

He drew the horses to a slow walk as they came to Hinckley Hill. It was a long pull and the steepest hill anywhere about. He stood with his hand on the brake and when they came to the first thank-you-ma'am he set it hard and shouted, "Whoa!" The horses flanks were heaving and he gave them a long breathing spell. Several times he did this before they reached the top. When they pulled over the top of the last grade, which seemed to be the steepest, he looped the lines around the standard and climbed down.

There were no houses anywhere near. He went to the back of the wagon. "You men want to get out and stretch a bit? Don't want to wear your bellies clear out lying flat on them that way."

He loosened the check reins and let the horses crop the grass beside the road.

Presently the men were stowed away again. He reined up the horses and climbed to his place. "Gee up there," he said and drew them to the middle of the road.

The moon, like fire, rose behind him and threw his shadow far ahead of the horses. Another load of free men, once slaves, rolled up the road to Freedom.

THE ELLSWORTH FAMILY

Unfortunately we do not have any family stories about the Ellsworth's direct involvement in transporting freed slaves. But we do know how they hid them.

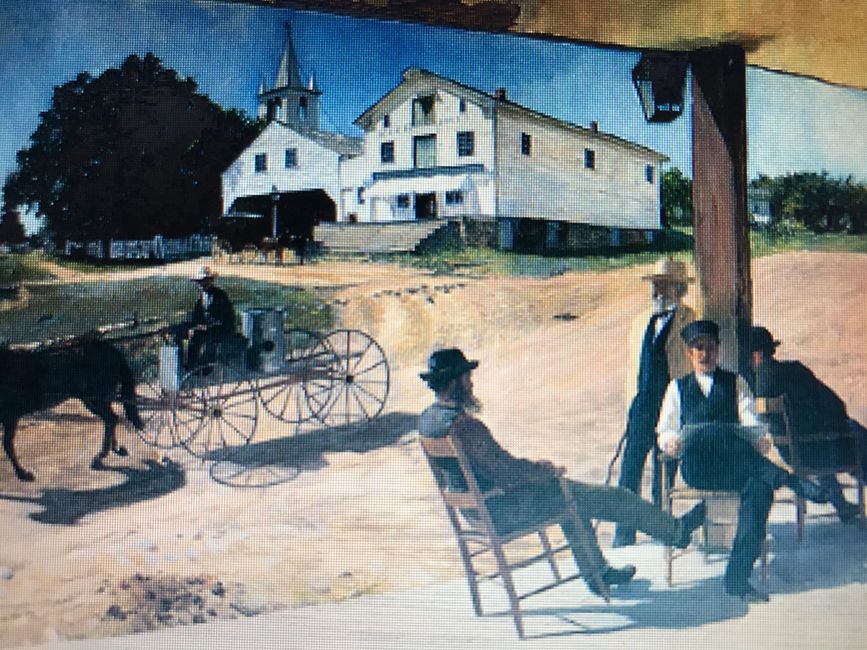

T. E. Ellsworth (sometimes called the "Father of West Richfield") and his family lived near the center of town in a Federal style house built in 1821. They added an addition sometime before the Civil War. John Brown's family lived fairly nearby, and the Ellsworth & Brown boys played together.

The Ellsworth house was a very short walk from the Tavern, just across the road from the Township Hall and next to many businesses, all clustered about the crossing of Broadview & Streetsboro Roads. In all the Township this was the busiest place there was. There were constant passersby all day. And always the possibility of late night strollers and wanderers. It had to have been a very tough place to hide, then transport, freed slaves along the Underground.

One hundred and twenty some years later, the newest owners of the Ellsworth house were doing some renovations on the Ellsworth's long ago winter kitchen, dining room and attic additions. They accidently discovered the attic walls popped off. This revealed long narrow hiding spaces running the entire length of each side of the attic. There they found remnants of old clothing and newspapers, proving their use before the war. Each of the hidden spaces on either side of the attic were large enough to hold 10 freedom seekers as they sat waiting to be spirited along to the next stop on the Underground. There may have been a hidden dumbwaiter that carried food to the hiding places from the downstairs kitchen.

John Brown's house was rather well located for wagons to stop by late at night. There were few neighbors and deep woods surrounded his property, so he was able to load his "cargo" in relative safety. But Ellsworth's was in the middle of town with close neighbors and much traffic. They had space for 20 people to hid, but a much more difficult situation in which to move them. But behind the Ellsworth's was deep woods (now known these days as Richfield Woods Park). A somewhat likely guess is that there were trails through the woods so the escaped could walk in either direction to a safer place to load.

THE PALMER FAMILY

Ebenezer Palmer was born in 1794 in Vermont. He died a long time Richfield resident in 1856. He was a well known and important man in the Township. He had apprenticed as a carpenter and when he had learned his trade, became an expert builder and joiner. Many of the houses and barns that were built in that era that replaced the original log cabins, were erected by Ebenezer. He much preferred building two stories than one because you got more space for the same roof. He worked for a dollar a day. He most likely helped build the "new" Congregational Church (of which he was a member) when the original one burned down in the 1830's. He also traveled to nearby communities, including Copley, to ply his trade, often carrying his heavy tool box on his shoulder on the long walks to work. He was known to be on his way to work long before the very early morning's first candles were lit in most of the cabins he passed.

Years later, sometime following WW2, his grand-daughter, Jennie Mackie Richie (1871-1961) wrote the family history that included the following:

"Grand-father Ebenezer had earnest Abolitionist friends. One in particular was wont to come pass the night in long discussion. He was John Brown, a good friend in the church, and one whom a few years before Mr. Palmer had made four coffins for the four Brown children who had died within a few days of the Scarlet Fever (Black Diphtheria in other accounts). They were buried in the Hill Cemetery (now East Cemetery) in Richfield."

THE FARNUM FAMILY & THE OHIO-ERIE CANAL

In ancient times the original peoples of what became Ohio followed the course of the Cuyahoga and Tuscaraugus Rivers to travel from the Great Lakes of the north to the Ohio River and farther south, all the way to what was later called the Gulf of Mexico. It was one of the most important trade routes of the ancient world.

Starting in 1825, the Ohio-Erie Canal was built following this river system. It opened the interior of Ohio so farmers could ship their goods to market. The Canal was one of the most important events of Ohio history. It enabled a sudden increase in Ohio's population when the canal opened, particularly along its course. "Lord" Farnum, who had been a special agent to George Washington during the war, was one of those farmers. His estate was to grow to 3,200 acres when his son, Everett, took over in 1834 and it gave the Farnum's the largest holdings in Summit Co. They raised as many as 3,000 sheep. They hired John Brown to manage the shearing.

There was one primary reason for the Canal. To ship and deliver goods. We know the Farnum's and the Oviatt's were the largest producers of farm products in the several counties, producing tons of wool and meat a year. We also know that John Brown produced large amounts of leather and wool. And all of it needed to be shipped to the East Coast cities.

We don't yet have a clear record of the Ohio-Erie Canal being used to smuggle the escaped to freedom. We do know the Miami & Erie Canal was. We know two major Underground Railroad routes passed along the Ohio-Erie Canal. In talking with the Chief Historian at the National Freedom Museum we feel very confident that the canal through Peninsula, just down the hill from Richfield, was also used as an escape route.

Everett Farnum was a member of the Richfield Congregational Church. He donated land for the cemetery where John Brown's four children are buried. He was friends with and employed John Brown. John Brown hauled Farnum's wool to the Canal, using the same wagon used at other times to deliver "cargo" to Oberlin. It seems very likely the Farnam's were also Abolitionist's, working to free the oppressed, just as "Lord" Farnam years earlier had so closely worked with Gen'l Washington to free a nation.

THE HURLBURT FAMILY

When J. E. Hurlburt and his wife sought to join the Richfield Congregational Church, they were asked: "Would you assist in returning a fugitive slave?"

J.E. replied in writing, saying (in part): "No man abhors the system of human slavery more than I do. I consider it an unmitigated wrong. Should any master of a slave, in pursuit of a fugitive, request or demand my assistance I should treat it with contempt and absolutely refuse. I would render the escaping slave all the assistance in my power in such circumstances to make his escape good." ~The Hurlburt's were duly admitted into the church.

THE HEMAN OVIATT FAMILY

The Oviatt's used their home, at 4284 West Streetsboro Rd., as a safe house on the Underground Railroad. A slave box, disguised to look like a fake clothes closet, was built in the basement. The escaped crawled into the attic and then slid down a wooden slide into the closet space. They stood there until they were relocated by the dark of night. The concealed space is now a bedroom closet and the wooden slide is gone, but evidence of the structures remain.

SCOBIE HOUSE

The Scobie house and farm, on Broadview Rd., is one of the most interesting of the possible UGRR stops in Richfield. Interesting because so much is said and believed, while so little is known. It almost perfectly illustrates the difficulty so often found in these more recent times, in making a record of events 160 years ago. For as written in a book by K. Morton, "There is little use in wondering when there is no one left to ask. They are all gone. They are all long gone. And the questions remain. Knots that can never be untied. Turned over and over again, forgotten by all."

I have known the last of the Richfield Scobie's most of my life. Harold was just a year ahead of me in grade school, and if I remember correctly, we attended Church and boy scouts at the same time. We've been nodding friends all these many decades. Sometimes closer, ofttimes less. And of course I knew his mom. A lot of it was just ~"old Richfield knowing old Richfield".

But despite the history we have shared, he grew quite upset when I drove in his drive one day this past winter. He really doesn't seem to like visitors. By repute, he invites very few into the house, but we talked for a bit, standing in his driveway. He said that he was simply tired of "strangers" driving in his drive over the last seventy years to ask about the UGRR. Nevertheless, after a time he admitted that he had heard many family stories of the UGRR in Richfield. When he was young he used to sit in the backseat of the family car, on drives to town, and listen to the old folks talk about the Underground and the old days. But he refused to recount any of those stories. He said they were just stories and he couldn't prove them, so he wouldn't tell them. ~~The problem with such an attitude was that so few stories were recorded about the UGRR, it was just too dangerous at the time. So stories were passed down as oral tradition. And when Harold is gone, his family's story's may finally disappear forever as well. Because even faint memories, unless recorded, will become lost memories. So for now, what we are left with, are stories told by other families about the Scobie House.

The Scobie house is one of the finer old brick homes in Richfield. Nearby still stand a number of the farm buildings and sheds. The barn, silos, and windmill are gone. But it seems apparent where they once stood. As you pass by on what is now called Broadview Rd. you would never know the farm was there. All that can be seen is a thick tangle of trees and a long gravel driveway. There is nothing of house or buildings visible. It seems a perfect place for "hiding".

Local legend has it that the Scobie Farm was a fairly well used stop on the UGRR. Most everyone who was "old Richfield" has heard those stories. But, Harold himself insists that he has never found any evidence of a hiding space. But the problem is that most often those secret rooms or spaces were long ago removed in most homes and barns because of the danger they posed if found. And quite often Underground stops simply didn't have special hidden places. The escaped just hid in a house attic or cellar (as at the John Brown and the Oviatt house's over on Streetsboro Rd.) or hid in the granary or crib in the barn.

So by legend the Scobie was a stop. By common modern day story it was a stop. But, by family history, we may never know. Harold's need for physical proof, and for privacy, seems to have outweighed any desire to record what the older generations of his family repeated of what an even earlier generation had told them.

~~I recently talked with Carl Westmoreland, chief historian of the National Underground Railroad Freedom Center located in Cincinnati, Ohio. He told me that in 1931 his father had been hired to work on the Dunagan Farm in Richfield. His dad took the train to Peninsula, the nearest stop on the railroad to Richfield. Unfortunately the train was delayed and he arrived at night, long after his scheduled arrival. The farm manager had given up waiting and returned home, thinking young Westmoreland would arrive the next day. When Carl's dad stepped to the platform in the dark of night, there was no one there. , … and it was a long walk to the farm. It might have been a bit like his ancestors had felt a hundred years before. Alone, in the dark, no one friendly to greet him, not knowing what was next.

Fortunately, a fellow from Richfield happened by and offered him a ride. As they drove up the long hill to town they talked about the stories the Richfield man had heard as a kid, about those older Richfield Abolitionists. And how those earlier men had taken the opportunity to help others in need. A chance meeting, and an occasion to relive a history that had taken place a hundred years before, of two people who might have thought they ordinarily wouldn't have much in common.

Copyright © Jim Fry 2018