Words that so effected john Brown, and all of america

"They are not human..."-anonymous slave owner

In Their Words

Nat Turner was an African-American slave who led a two-day rebellion of slaves and free blacks in Southampton County, Virginia on August 21, 1831. The rebellion caused the death of approximately sixty white men, women and children. Whites organized militias and called out regular troops to suppress the uprising. In addition, white militias and mobs attacked blacks in the area, killing an estimated 120, many of whom were not involved in the revolt. Nobody was arrested, tried or executed for these crimes against black men, women and children.

~

"I had a vision - and I saw white spirits and black spirits engaged in battle, and the sun was darkened - the thunder rolled in the Heavens, and blood flowed in streams - and I heard a voice saying, 'Such is your luck, such are you called to see, and let it come rough or smooth, you must surely bear it."

"After having supplied myself with provisions from Mr. Travis's, I scratched a hole under a pile of fence rails in a field, where I concealed myself for six weeks, never leaving my hiding place but for a few minutes in the dead of night to get water, which was very near."

"When I got large enough to go to work, while employed I was reflecting on many things that would present themselves to my imagination; and whenever an opportunity occurred of looking at a book, when the school-children were getting their lessons, I would find many things that the fertility of my own imagination had depicted to me before."

Ellen Craft was a slave from Macon, Georgia who escaped to the North in 1848. Craft, the light-skinned daughter of a mulatto slave and her white master, disguised herself as a white male planter. Her husband William Craft accompanied her, posing as her personal servant. She traveled openly by train and steamboat, arriving in Philadelphia on Christmas Day 1848. Her daring escape was widely publicized, and she became one of the most famous fugitive slaves.

~

"It is true, our condition as slaves was not by any means the worst; but the thought that we could not call the bones and sinews that God gave our own, and the fact that another man had the power to tear from our cradle the new-born babe and sell it like a brute, then scourge us if we dared to lift a finger to save it from such a fate; haunted us for years."

"I had much rather starve in England, a free woman, than be a slave for the best man that ever breathed upon the American continent."

Harriet Tubman was an American abolitionist and political activist. Born into slavery, Tubman escaped and subsequently made some thirteen missions to rescue approximately seventy enslaved people, family and friends, using the network of antislavery activists and safe houses known as the Underground Railroad. She later helped abolitionist John Brown recruit men for his raid on Harpers Ferry. During the American Civil War, she served as an armed scout and spy for the United States Army. In her later years, Tubman was an activist in the struggle for women's suffrage.

~

"I had reasoned this out in my mind, there was one of two things I had a right to, liberty or death; if I could not have one, I would have the other."

"I would fight for my liberty so long as my strength lasted, and if the time came for me to go, the Lord would let them take me."

Sojourner Truth was an African-American abolitionist and women's rights activist. Truth was born into slavery in Swartekill, Ulster County, New York, but escaped with her infant daughter to freedom in 1826. After going to court to recover her son in 1828, she became the first black woman to win such a case against a white man.

~

"We do as much, we eat as much, we want as much."

David Walker was an African-American abolitionist, writer, and anti-slavery activist. Though his father was a slave, his mother was free so therefore he was free. In 1829, while living in Boston, Massachusetts, with the assistance of the African Grand Lodge, he published An Appeal to the Coloured Citizens of the World, a call for black unity and self-help in the fight against the oppressive and unjust slavery.

~

"Treat us like men, and there is no danger but we will all live in peace and happiness together. For we are not like you, hard hearted, unmerciful, and unforgiving. What a happy country this will be, if the whites will listen."

Journalist Martin Robison Delany was an African-American abolitionist, journalist, physician, soldier and writer, and arguably the first proponent of black nationalism. Delany is also credited with the Pan-African slogan "Africa for Africans." He was the author of : The Origins of Race and Color.

~

"Every people should be originators of their own destiny."

Site Content

Maria W. Stewart was an American domestic servant who became a teacher, journalist, lecturer, abolitionist, and women's rights activist. The first known American woman to speak to a mixed audience of men and women, whites and black, she was also the first African-American woman to make public lectures, as well as to lecture about women's rights and make a public anti-slavery speech.

~

"..It is not the color of the skin that makes the man or the woman, but the principle formed in the soul. Brilliant wit will shine, come from whence it will; and genius and talent will not hide the brightness of its lustre."

"Look at many of the most worthy and interesting of us doomed to spend our lives in gentlemen's kitchens. Look at our young men, smart, active and energetic, with souls filled with ambitious fire; if they look forward, alas! what are their prospects? They can be nothing but the humblest laborers, on account of their dark complexions."

"Most of our color have been taught to stand in fear of the white man from their earliest infancy, to work as soon as they could walk, and to call "master" before they scarce could lisp the name of mother. Continual fear and laborious servitude have in some degree lessened in us that natural force and energy which belong to man; or else, in defiance of opposition, our men, before this, would have nobly and boldly contended for their rights ... give the man of color an equal opportunity with the white from the cradle to manhood, and from manhood to the grave, and you would discover the dignified statesman, the man of science, and the philosopher. But there is no such opportunity for the sons of Africa ... I fear that our powerful ones are fully determined that there never shall be ... O ye sons of Africa, when will your voices be heard in our legislative halls, in defiance of your enemies, contending for equal rights and liberty? ... Is it possible, I exclaim, that for the want of knowledge we have labored for hundreds of years to support others, and been content to receive what they chose to give us in return? Cast your eyes about, look as far as you can see; all, all is owned by the lordly white, except here and there a lowly dwelling which the man of color, midst deprivations, fraud, and opposition has been scarce able to procure. Like King Solomon, who put neither nail nor hammer to the temple, yet received the praise; so also have the white Americans gained themselves a name, like the names of the great men that are in the earth, while in reality we have been their principal foundation and support. We have pursued the shadow, they have obtained the substance; we have performed the labor, they have received the profits; we have planted the vines, they have eaten the fruits of them. "

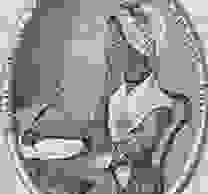

Poet Phillis Wheatley was the first published African-American female poet. Born in West Africa, she was sold into slavery at the age of seven or eight and transported to North America. She was purchased by the Wheatley family of Boston, who taught her to read and write and encouraged her poetry when they saw her talent.

~

"Aurora hail, and all the thousand dies,

Which deck thy progress through the vaulted skies:

The morn awakes, and wide extends her rays,

On ev'ry leaf the gentle zephyr plays;

Harmonious lays the feather'd race resume,

Dart the bright eye, and shake the painted plume."

Olaudah Equiano, known in his lifetime as Gustavus Vassa, was a writer and abolitionist from the Igbo region of what is today southeastern Nigeria according to his memoir, or from South Carolina according to other sources. Enslaved as a child, he was taken to the Caribbean and sold as a slave to a captain in the Royal Navy, and later to a Quaker trader. Eventually, he earned his own freedom in 1766 by intelligent trading and careful savings.

~

"Is it not enough that we are torn from our country and friends, to toil for your luxury and lust of gain? Must every tender feeling be likewise sacrificed to your avarice?"

"The first object which saluted my eyes when I arrived on the coast was the sea, and a slave ship, which was then riding at anchor, and waiting for its cargo. These filled me with astonishment, which was soon connected with terror, when I was carried on board. I was immediately handled, and tossed up to see if I were sound, by some of the crew; and I was now persuaded that I had gotten into a world of bad spirits, and that they were going to kill me."

unknown slave-1789

I am one of that unfortunate race of men who are distinguished from the rest of the human species by a black skin and woolly hair—disadvantages of very little moment in themselves, but which prove to us a source of greatest misery, because there are men who will not be persuaded that it is possible for a human soul to be lodged within a sable body. The West Indian planters could not, if they thought us men, so wantonly spill our blood; nor could the natives of this land of liberty, deeming us of the same species with themselves, submit to be instrumental in enslaving us, or think us proper subjects of a sordid commerce. Yet, strong as the prejudices against us are, it will not, I hope on this side of the Atlantic, be considered as a crime for a poor African not to confess himself a being of an inferior order to those who happen to be of a different color from himself, or be thought very presumptuous in one who is but a Negro to offer to the happy subjects of this free government some reflection upon the wretched condition of his countrymen. They will not, I trust, think worse of my brethren for being discontented with so hard a lot as that of slavery, nor disown me for their fellow creature merely because I deeply feel the unmerited sufferings which my countrymen endure.

It is neither the vanity of being an author, nor a sudden and capricious gust of humanity, which has prompted this present design. It has long been conceived and long been the principal subjects of my thoughts. Ever since an indulgent master rewarded by youthful services with freedom and supplied me at a very early age with the means of acquiring knowledge, I have labored to understand the true principles on which the liberties of mankind are founded, and to possess myself of the language of this country in order to plead the cause of than who were once my fellow slaves, and if possible to make my freedom, in some degree, the instrument of their deliverance.

The first thing, which seems necessary in order to remove those prejudices which are so unjustly entertained against us is to prove that we are men—a truth which is difficult of proof only because it is difficult to imagine by what argument it can be combated. Can it be contended that a difference of color alone can constitute a difference of species?—If not, in what single circumstance are we different from the rest of mankind? What variety is there in our organization? What inferiority of art in the fashioning of our bodies? What imperfection in the faculties of our minds?—Has not a Negro eyes? has not a Negro hands, organs, dimensions, senses, affections, passions?—fed with the same food; hurt with the same weapons; subject to the same diseases; healed by the same means; warmed and cooled by the same summer and winter as a white man? If you prick us, do we not bleed? If you poison us, do we not die? Are we not exposed to all the same wants? Do we not feel all the same sentiments—are we not capable of all the same exertions—and are we not entitled to all the same rights as other men?

Yes—and it is said we are men, it is true; but that we are men addicted to more and worse vices than those of any other complexion; and such is the innate perverseness of our minds that nature seems to have marked us out for slavery.—Such is the apology perpetually made for our masters and the justification offered for that universal proscription under which we labor.

But I supplicate our enemies to be, though for the first time, just in their proceedings toward us, and to establish the fact before they attempt to draw any conclusions from it. Nor let them imagine that this can be done by merely asserting that such is our universal character. It is the character, I grant, that our inhuman masters have agreed to give us and which they have so industriously and too successfully propagated in order to palliate their own guilt by blackening the helpless victims of it and to disguise their own cruelty under the semblance of justice. Let the natural depravity of our character be proved—not by appealing to declamatory invectives and interest representations, but by showing that a greater proportion of crimes have been committed by the wronged slaves of the plantation than by the luxurious inhabitants of Europe, who are happily strangers to those aggravated provocations by which our passions are every day irritated and incensed. Show us that, of the multitude of Negroes who have within a few years transported themselves to this country, and who are abandoned to themselves; who are corrupted by example, prompted by penury, and instigated by the memory of their wrongs to the commission of crimes show us, I say (and the demonstration, if it be possible, cannot be difficult), that a greater proportion of these than of white men have fallen under the animadversions of justice and have been sacrificed to your laws. Though avarice may slander and insult our misery, and though poets heighten the horror of their fables by representing us as monsters of vice—that fact is that, if treated like other men, and admitted to a participation of their rights, we should differ from them in nothing, perhaps, but in our possessing stronger passions, nicer sensibility, and more enthusiastic virtue.

Before so harsh a decision was pronounced upon our nature, we might have expected—if sad experience had not taught us to expect nothing but injustice from our adversaries—that some pains would have been taken to ascertain what our nature is; and that we should have been considered as we are found in our native woods rend not as we now are—altered and perverted by an inhuman political institution. But instead of this, we are examined, not by philosophers, but by interested traders; not as nature formed us, but as man has depraved us—and from such an inquiry, prosecuted under such circumstances, the perverseness of our dispositions is said to be established. Cruel that you are! you make us slaves; you implant in our minds all the vices which are in some degree inseparable from that condition; and you then impiously impute to nature, and to God, the origin of those vices, to which you alone have given birth; and punish in us the crimes of which you are yourselves the authors.

The condition of the slave is in nothing more deplorable than in its being so unfavorable to the practice of every virtue. The surest foundation of virtue is love of our fellow creatures; and that affection takes its birth in the social relations of men to one another. But to a slave these are all denied. He never pays or receives the grateful duties of a son he never knows or experiences the fond solicitude of a father—the tender names of husband, of brother, and of friend, are to him unknown. He has no country to defend and bleed for—he can relieve no sufferings—for he looks around in vain to find a being more wretched than himself. He can indulge no generous sentiment—for he sees himself every hour treated with contempt and ridiculed, and distinguished from irrational brutes by nothing but the severity of punishment. Would it be surprising if a slave, laboring under all these disadvantages¬—oppressed, insulted, scorned, trampled on—should come at last to despise himself—to believe the calumnies of his oppressors—and to persuade himself that it would be against his nature to cherish any honorable sentiment or to attempt any virtuous action? Before you boast of your superiority over us, place some of your own color (if you have the heart to do it) in the same situation with us and see whether they have such innate virtue, and such unconquerable vigor of mind, as to be capable of surmounting such multiplied difficulties, and of keeping their minds free from the infection of every vice, even under the oppressive yoke of such a servitude.

But, not satisfied with denying us that indulgence, to which the misery of our condition gives w so just a claim, our enemies have laid down other and stricter rules of morality to judge our actions by than those by which the conduct of all other men is tried. Habits, which in all human beings except ourselves are thought innocent, are, in us, deemed criminal—and actions, which are even laudable in white men, become enormous crimes in Negroes. In proportion to our weakness, the strictness of censure is increased upon us; and as resources are withheld from us, our duties are multiplied. The terror of punishment is perpetually before our eyes; but we know not how to avert, what rules to set by, or what guides to follow. We have written laws, indeed, composed in a, language we do not understand and never promulgated: but what avail written laws, when the supreme law, with us, is the capricious will of our overseers? To obey the dictates of our own hearts, and to yield to the strong propensities of nature, is often to incur severe punishment; and by emulating examples which we find applauded and revered among Europeans, we risk inflaming the wildest wrath of our inhuman tyrants.

To judge of the truth of these assertions, consult even those milder and subordinate rules for our conduct, the various codes of your West India laws—those laws which allow us to be men, whenever they consider us as victims of their vengeance, but treat us only like a species of living property, as often as we are to be the objects of their protection those laws by which (it may be truly said) that we are bound to suffer and be miserable under pain of death. To resent an injury received from a white man, though of the lowest rank, and to dare to strike him, though upon the strongest and grossest provocation, is an enormous crime. To attempt to escape from the cruelties exercised upon us by flight is punished with mutilation, and sometimes with death. To take arms against masters, whose cruelties no submission can mitigate, no patience exhaust, and from whom no other means of deliverance are left, is the most atrocious of all crimes, and is punished by a gradual death, lengthened out by torments so exquisite that none but those who have been long familiarized with West Indian barbarity can hear the bare recital of them without horror. And yet I learn from writers, whom the Europeans hold in the highest esteem, that treason is a crime which cannot be committed by a slave against his master; that a slave stands in no civil relation towards his master, and owes him no allegiance; that master and slave are in a state of war; and if the slave take up arms for his deliverance, he acts not only justifiably but in obedience to a natural duty, the duty of self preservation. I read in authors whom I find venerated by our oppressors, that to deliver one's self and one's countrymen from tyranny is an act of the sublimest heroism. I hear Europeans exalted as the martyrs of public liberty, the saviors of their country, and the deliverers of mankind—I see other memories honored with statues, and their names immortalized in poetry—and yet when a generous Negro is animated by the same passion which ennobled them—when he feels the wrongs of his countrymen as deeply, and attempts to avenge them as boldly—I see him treated by those same Europeans as the most execrable of mankind, and led out, amidst curses end insults, to undergo a painful, gradual and ignominious deer. dad thus the same Briton, who applauds his own ancestors for attempting to throw off the easy yoke imposed on them by the Romans, punishes us, as detested parricides, for seeking to get free from the cruelest of all tyrannies, and yielding to the irresistible eloquence of an African Galgacus or Boadicea.

Are then the reason and morality, for which Europeans so highly value themselves, of a nature so variable and fluctuating as to change with the complexion of those to whom they are applied?—Do rights of nature cease to be such when a Negro is to enjoy them?—Or does patriotism in the heart of an African rankle into treason?

Copyright © Jim Fry 2018